One ice night in 1941, prisoners of Stalag VIII-A, a Nazi Labor in Silesia, gathered in an unheated bathroom to listen to a musical performance. It was an unusual event, and not only because of the place.

Written by the French composer Olivier Messiaen, the quartet was noted for piano, clarinet, violin and cello, an unconventional combination which was born from the need: it is the Messiaen instruments and its three scholarships Prisoners of war could play. Performance has brought the modern and modernist modern Quartet for the end of time in the world and remembers one of the most consecutive first musicals of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the Novachord – the first commercial polyphonic synthesizer – had recently been unveiled. It was welcomed, as the new technology is often, panic. Would this machine make humans obsolete in musical composition?

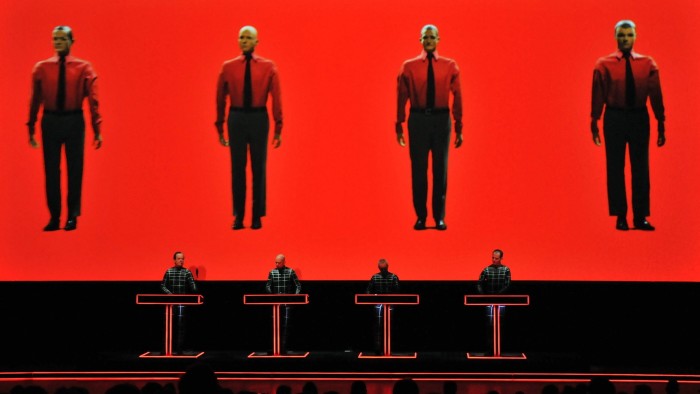

Today, we know the answer: the synthesizers who followed the Novachord largely widens the sounds available for composers and DJs, have given birth to new kinds of popular music and have become an essential means of musical creation. We would not have hip-hop or seminal albums such as Radiohead Kid has Without them. At the same time, today's musicians are confronted with a new technology of encroachment: artificial intelligence, by its power to replace their voices, to circumvent education and to suppress human surveillance.

The more the technology tries to reproduce the qualities that we identify as us only human – think, feel, create – that is to say, the more it claims to act in our image, the more we tend to fear it. And yet, it is enough to take a look at a work of art generated by AI, then to watch a painting Cy Twombly – or to listen to the Messiaen Quartet – to be relieved of these concerns. The distinction becomes clear as the day. A work of art approaches human expression. The other East Human expression.

To what extent should we be worried about technological disruption? And will he one day make the creatives obsolete in the manufacture of art? These questions circulate as long as humans have made machines, but what happens if they are bad? The two new books considered here – The strange muse by David Hajdu and Quartet for the end of time By Michael Symmons Roberts – Offer distinctive approaches to explore how human creativity reacts to its changing environment. Can apparently existential challenges become constituent elements of the creative process?

In Quartet for the end of timeThe meditation of Symmons Roberts on his sorrow for his parents reflected and flows with the history of the Messiaen Quartet – his creation, his historical resonance, his personal meaning for him – an underground river on the surface. Symmons Roberts is a long -standing British poet, novelist and free novelist, making this book a careful confluence of his talents: it is a romantic memory, between his own poems, which always returns to the music of Messiaen. He discovered the quartet by chance while browsing a record store in the 1980s as a student, becoming, from this moment, a “listener for life” of the play.

Before being interned in the camp at the start of the thirties, Messiaen's musical reputation had been in the ascendancy in Paris. Symmons Roberts describes it as a “mystical modernist composer”, a “Catholic visionary, an obsessive ornithologist”, which has written radically, inventively modern – of which this quartet is the crowned example.

Part of the Symmons Roberts investigation demystifies some of the myths surrounding its genesis. For example, his first at the camp would have been carried out on beaten and beaten instruments. However, according to Eyewitness testimonies, a new cello was bought in the neighboring city of Görlitz for performance. The captivated public of suffering prisoners was not united in his appreciation; Some hated the atonality of work. And often supervised in response to war, the play was in fact inspired by the apocalyptic visions of St John the Divine in the book of Apocalypse-which promised, in the eyes of Messiaen, “a glorious world of love beyond this world, beyond the end of time”.

These clarifications are important. Above all, Messiaen did not consider his restrictive situation but affirmed that among all the prisoners, he “was probably the only one to be free”. Its constrained environment has not reduced its creative work, it improved it.

Opening to the first show of algorithmic art in New York in 2019, Hajdu's Lively The strange muse Trace the relationship between human creativity and mechanical or technological innovations since the end of the 19th century. Hajdu, an American music critic and journalism professor, writes that “in the manufacture of music, the dynamics of the human machine has always been more than a philosophical vanity. It is a practical consideration. “

From the advent of autonomous pianos at the beginning of the 20th century to the “automatic reproduction” of Andy Warhol – the printing of screen -based screen to create several impressions, one after the other – Hajdu argues that many technologies initially seen with suspicion were finally incorporated into artistic practice at an enriching effect. It recounts the cultural evolution of machines in the arts in a broader history that most will recognize, such as the development of B-3 electric organs in the 1950s, which became the sound of Gospel music; Martin Luther King Jr preached with electrical organs in the background.

But it is increasingly difficult in 2025 to see new technologies without buckets of skepticism, knowing that we are in an unexplored territory with regard to generating AI, people who control it and the threat to the means of subsistence of artists. On the one hand, the restoration tools use AI to recover historical recordings, such as the isolation of John Lennon's voice on a Beatles demo “”From time to timeIn 2023, or the production company of director Peter Jackson, Wingnut Films, developing his own “undressing” software from the AI which could deposit intertwined sounds. On the other hand, this may devalue musical work as production studios increase their use of AI.

And yet, appearing our concerns is not Hajdu's point. Neither rejecting technological innovation as a threat to authentic human expression nor celebration without criticism, he argues that we consider the human-machine binary as a “collaboration”. Inventions such as recording technology, which artists feared formerly would eliminate live performance, evolved into sophisticated art forms in itself; He quotes Sgt. PEPPER SOLARITY COURSURS GROUP As “totem of the recording studio as an instrument” and turntables as the main instrument of “Hip-hop DJ … Innovate an original sound vocabulary”. If you like to listen to electronic music or buy reproductive posters in museum gift shops, you will likely agree that technology has expanded rather than contracted by artistic possibilities, as well as music and other art forms to a wider audience.

Symmons Roberts maintains that for Messiaen, his strange constellation of instruments forced him to mix the tones of the quartet in a completely new way. The layers of sound were unprecedented, but they worked, which makes the instrumental palette limited not an obstacle but essential to the character of the work. It is enough to listen to the first movement of the quartet, “liturgy of crystal”, to hear the clarinet play figures inspired by birds which hover over the percussive piano and the silky rope; A multilayer sonic plan. As Symmons Roberts writes, it is “as sticking the head in a surreal aviary in which birds sound as if they have eaten fermented fruit. It is not only a bird either, all the instruments are there. There was no going back. ”

Symmons Roberts, efforcing the connection that Messiaen, a “connoisseur of bird song”, felt with natural world music, uses a “Bird ID application” to identify the individual sounds making up the dawn choir outside of his house. The technology developed by AI brings it closer, as Messiaen considered the song of birds, “the authentic music of Eden”.

After being released from the camp, Messiaen returned to Paris and became one of the most estimated composers of the 20th century, living until the age of 83. However, Symmons Roberts does not present a simplistic story of triumph of adversity, just as Hajdu does not offer any clear solution to overcome our potential adversary in AI. The swirling tour of the latter for almost 150 years of cultural history is both Pacy and overflowing with details. I had no idea, for example, that Bach onA 1968 synthesizer of JS Bach by Wendy Carlos, was loved by the venerated pianist Glenn Gould, who described the record for “one of the great exploits in the history of” keyboard “performance” – leaving the reader a feeling of optimism of what could expect.

The prose of Symmons Roberts, on the other hand, is silky and emotional, with its success in the weaving of personal shutters with the musical in part due to the deep connections forged by its poems, each apparently chosen to increase our understanding of what precedes it.

This creativity is in constant dialogue at the same time with our expression and our circumstances is the thread that connects the two books, and reading the Oulipo, the experimental collective of French writers who has imposed artificially constraints in order to extend creativity: with the imposed limits, their theory, we can access new areas of creative freedom.

None of the two books offer a resolution as such, but reading them in parallel offers two ways of the idea that overcoming it is not always the most generative posture. This true generative artistic power is rather to cultivate ingenuity to exploit the challenges we are faced with.

The Uncanny Muse: Music, art and machine machines at AI by David Hajdu WW NORTON £ 25 / $ 32.99, 304 pages

Quartet for the end of time: on music, sorrow and the song of birds by Michael Symmons Roberts Jonathan Cape £ 20, 304 pages

Join our online books online on Facebook in Ft Books Coffee And follow the FT weekend on Instagram And X