Unlock the publisher's digest free

Roula Khalaf, editor -in -chief of the FT, selects her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer, editor -in -chief of FT, is Director General of the Royal Society of Arts and former chief economist of the Bank of England

Panican: name. A person or a panic party, excessively reacting to events in a weak and stupid way. Derogatory.

This neologism has barely a month. There is an irony, a large part, that in the week following the invention, its author (the American president) had himself become a member who carries cards from the Panican party. It only took 24 hours of chaos of the bond market for the “Liberation Day” to give in to the “Comeuppance quarter”, with a price break of 90 days.

Nevertheless, the question raised by the American president remains so relevant at that time. Does the reaction of financial markets, politicians and the media at its pricing ads been excessive? Do catastrophizers 24/7 have financial and media markets, and a political class regularly declaring the end of the world, panicked?

The impact of prices, and in particular the fear of an unknown climbing in them, is in a very real important sense. If a arms race set up, a day of release may well predict a decade or more hibernation in trade and global growth. The arc of the history of trade has, with alarming regularity, folded towards the dark.

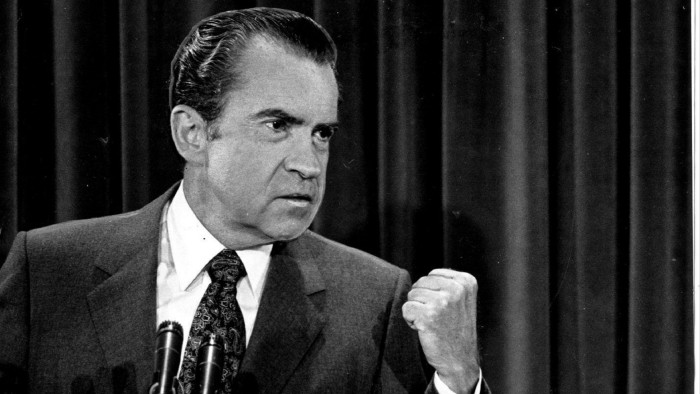

Price shocks emanating from the United States has occurred on a regularly half-century cycle in the last 250 years: 1789, 1828, 1890, 1930, 1971. Each has left a sustainable macroeconomic scar-in the case of the penultimate (the “Nixon Shawley Tariffs) moving the great depression. Both are stored as big for bad reasons.

Half a century later, with the world's now larger and much more intertwined, the scars of a pricing shock in 2025 should be even deeper. The economic forecasts stained with blood last month testify, with an American recession now a coin. The same goes for the financial markets, with more than 6 TN lost in the world's stock markets and implicit volatility that has tripled.

On the other side of this argument, however, no one is in doubt today that the cradle of the world cat supply channels can not be untangled without years of reenginery at the catastrophic cost. The very interconnectivity of global trade and disconnection costs are the best possible numbers against tariff climbing.

The excessive sensitivity of the financial markets applies a double locking. In telescopic and amplifying these costs, they serve as a real -time discipline device on politicians saying that they can resist short -term pain. This makes capitulation faster than in the past. The Smoot-Hawley prices lasted four years, the four months of the Nixon price. The worst price of Trump lasted barely a week.

The prices could be re -specified. But once bitten, twice shy. Last month leaves an American president as psychologically scars and the slim skin of Gossamer like the companies and the financial markets he held in Thrall. The irresistible force of self-importance has contributed to provoking the American tariff peak, but the real estate object of self-service will be its loss.

For all the rhetoric of a new world order, the forces of global average reversion can actually be stronger than ever. A new financial order was widely awaited after the global financial crisis. Twenty years later, we have seen a certain redirection of the flows, but no big detangling. Global trade may well follow a similar path, if something fortified by recent events, perhaps even with China as a new improbable champion.

Meanwhile, despite the external expressions of dismay, last month was a political boon for many world leaders. The trade war and discussions on a new world order breathe life for signaling and unpopular regimes (Xi Jinping in China, Emmanuel Macron in France, Vladimir Putin in Russia), offering alternatives ready for Oven for new ones (Friedrich Merz in Germany, Mark Carney in Canada, Keir Starmer in the United Kingdom).

However, revealing, and with the exception of China, the escalation solemnly declared by many leaders has so far been largely semantic rather than substantial. We had a month of reciprocal rhetoric rather than prices. If the forces of average reversion and self-preservation remain strong, perhaps (and will) which will continue.

A time of dis-aging is possible. Trump's prices can still mark a new commercial chapter. More likely, however, the arc of history will fall back to light, with recent events because the chapter feet not the headers. What we have seen is panic rather than a heart attack for the world economy – indeed, a self -stabilizer. In an era too anxious and without rudder, the rise of the panicans can save us from ourselves.