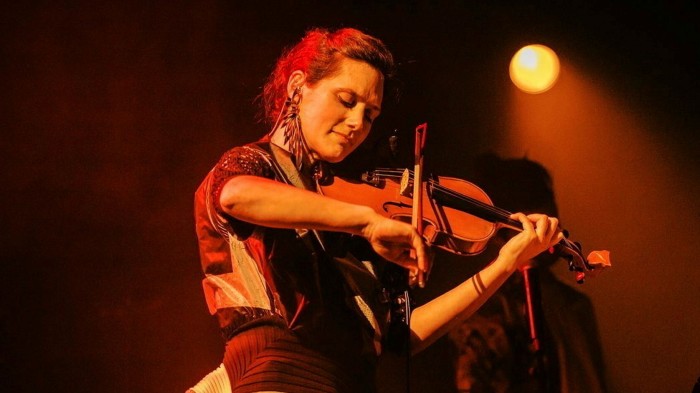

The first time I saw Rakhi Singh, she was barefoot, playing the violin in the Purcell room on Southbank in London. Singh directed Manchester Collective, the flexible group of classical musicians that she co-founded, in a concert by Oliver Leith, Caroline Shaw and shostakovich. The Shaw transfixed, the Shostakovich Embelling and Singh, which spoke to the public before each room, in soft order.

It would have been much more risky to be barefoot at the start of the existence of collective Manchester. Founded in 2016 with his friend Adam Szabo, the group organized concerts in the spaces, clubs and warehouses of artists, “Cold and Dark and Humit”, explains Singh when we meet in southeast London. “I remember some of the first shows playing with my coat and my hat. I couldn't wear a scarf because you can't really when you are a violinist. I had as many layers of clothes as possible.”

The strategy was partly a necessity – no polished place would take a whole new set – but also a choice to allow creativity, a way of making classical music differently. “There is something rather curious when you play something from its normal context,” explains Singh, 43.

“When you juxtapose things, it creates a certain energy. People were quite curious to come and see a concert of classical music and be able to drink a beer at the same time … We got rid of all the formalities and I think there was thirst and hunger for that. ” He feels “electric”.

Underground and outraged concert places have attracted a non -traditional audience. In a first concert in an old abandoned factory, says Singh, a ticket holder entered and exclaimed: “They have violins?!”

Since these days, the Manchester collective has entered the dominant current, playing concerts at the Southbank Center and Wigmore Hall, and winning the Prize of the Ensemble at the Royal Philharmonic Society Awards. But he also kept an adventure spirit, with a spot concert in a Shoredch club and, at the end of April, a two dates tour for RefractionsA “continuous and visual sound experience” mixes contemporary dance and classical and experimental music.

Singh's musical training did not make her an obvious candidate to bypass conventional subtleties. Born in the south of the Wales of an Indian father and an English mother, she won performance prizes in adolescence and attended the Royal Northern College of Music, before directing the Barbirolli String Quartet and the best British orchestras of advanced. But it felt limited by traditional study and concert programs: “As precious and interesting as studying the Haydn and Beethoven Quartets and the Brahms symphonies and the quarters of Bartók, there is still much more music to explore.”

Having had a young success, his career “collapsed after a certain time”, which strengthened the impulse “to make concerts … to play the music we want to play”. This included works of commissioning composers for a new flow of what it looked today, so Manchester Collective gave many world's first worlds like Laurence Osborn.

The whole has an unusual quality accordion type – it can extend according to the necessary sounds. In the concert of Purcell Room, there were 18 musicians on stage, but in a underground village in eastern London last summer, it was just violin, viola and cello for Imogen Holst and Errollyn WallenThe public on four sides around a small scene and the musicians sometimes appear behind or next to us. The only constant is Singh itself, both as a musician and underlie sensitivity.

When she designs concerts, it is not as simple as the opening-consternation-symphony formula that the orchestras behave. “Our programs are really chalk and cheese sometimes – or yin and yang, maybe I should say … I am not afraid to put things that I really know that some people will not like it,” says Singh. “But I will then make sure there is something against that. So everyone wins something new and it's not a bad thing to be uncomfortable sometimes, it's important.“”

Refractions Will imply another level of complexity of the collective efforts of previous Manchester, with 12 strings and a piano crossing a millennium of music as dancers, choreographed by Melanie Lane, interpreting it on stage. The last end will be recovered by the electronic musician Clark. Music from all times, for Singh, is communication. “When I relate to a piece of Hildegard von Bingen (a female composer from the 12th century), I have the impression of receiving a message from the past and living through the present,” she said. This is why everything belongs together: “He will plunge from Hildegard von Bingen to Techno, back to Bach, back to more cinematographic science fiction landscapes, to Beethoven.”

Singh has long experienced multimedia and interdisciplinary performance, so she says Refractions is the culmination of a work decade. It fits well in the modern movement where musicians and groups, such as Elaine Mitchener and bastard assignments, dissolve the boundaries between music, theater, cinema, performance and visual art.

This amorphride makes it difficult to speak. “I feel a bit like Michelangelo who makes” David “- he can see the thing inside the stone. But until everything is sculpted, it is very difficult to describe it, “says Singh. Nevertheless, he will have electronic and baroque dances, and an arc of “chaos and destruction (with) reflection and restoration then ecstasy”.

It is better to end with ecstasy, I say. Singh laughs: “It's always nice to go out at the top.”

“Refractions” are in Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, April 25 and the Southbank Center, London, April 26, manchestercollective.co.uk

Find out first of all our latest stories – Follow the FT weekend on Instagram And XAnd register To receive the FT weekend newsletter every Saturday morning