“There is no innocent card,” observes Philippe Rekacewicz in his catalog test that accompanies Diagrams, A new exhibition at the Prada Foundation in Venice.

Renowned cartographer, the Rekacewicz born in Paris is well aware of the capacity of its medium to transform the stories for good and the patients. His own work includes cards that illustrate the death of migrants when they submit new lives in Europe. “A map”, continues Rekacewicz, “is above all a social and political act – and therefore intrinsically subjective”.

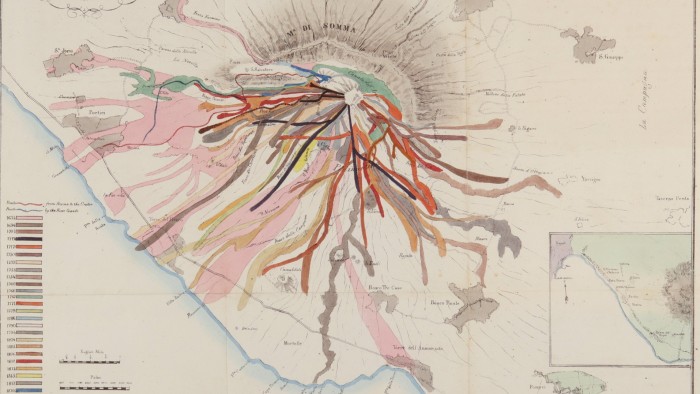

Organized by the international architect Rem Koolhaas and its studio Amo / Oma, The Prada Show aims to consider diagrams in all their political complexities. In addition to maps, the myriad of elements of the exhibition includes infographics from the beginning of the 20th century by the African-American web of wood sociologist highlighting racial inequalities; Chinese wooden engraving from the 17th century from the human circulatory system; And a 2008 Amo / Oma card itself showing the 10 main study destinations for students in China and the United States.

If this seems a dangerously wide field, this is deliberately the case. “We are not trying to map the whole trip,” explains the associate architect of OMA, Giulio Margheri. “We were looking for models.” The spectacle, known as Margheri, was thematic around “emergencies”, in particular the body, the built environment, inequality, migration, representation of the world, resources, war, truth and values.

Rather than delivering an omniscient chronological account, Margheri says that the goal was to “provide moments and episodes”. These are “made more powerful by the association between them,” he continues. “It was exciting to see how subjects were talking over time.”

For example, in the section devoted to the human body, Chinese wood engravings are juxtaposed to contemporary images. “The information we have on the body change,” observes Margheri, adding that, in previous times, observation and dissection were the only forms of investigation as opposed, for example, to modern radiography. But, overall, the body itself remains unchanged, making similarities between images such as lighting than differences.

Mainly, diagrams are information platforms. “Some people seem boring,” admits Margheri. “But by the minute you study them, you get another layer of understanding.” This is certainly true for an print in 1869 clocking the trip of Hannibal of Spain through the south of France and through the Alps in Italy by the French civil engineer and infographic pioneer Charles Joseph Minard. Composed of a beige group oscillating through a white space almost without relief – with the exception of place names, thinning pen shots of delimiting hair and a few hatching lines meaning the Mediterranean – it does not reveal anything at the first glance of the rollerère of the death of General Carthaginians while he, his army and his elephants took place and awarded by elephants who were awarded and rocks and deadly rivers and elephants. But when considered in the light of these challenges, it becomes captivating.

Minard, who died in 1870, struck his stride in the 19th century, when Diagrams“The conservatives describe as the golden age of infographics. His diagram of Napoleon's campaign in Russia Cartaque retreat through Poland according to the amazing assessment of his army and the temperatures below zero. While men die, the Graphic Beige Group of Minard shrinks, offering a visual cold at the Carillon with this time in Eastern Europe.

Other images are also revealing for what they hide. Consider the diagram entitled “Universal Commercial History”, a visual analysis written by the Scottish engineer William Playfair in 1805 which traces the rise and the fall of world wealth since 1500 BC against what he calls “remarkable events compared to trade”. Playfair, which would have invented the pie graph, includes moments such as “Rome Foundted”, “Muhammad's Flight” and “America Discown”. He never mentions slavery.

With such a broad approach, the gaps are inevitable. It is a shame that the work of Viennese social specialist Otto Neurath – who, with his wife Marie and his colleague Gerd Arntz, invented the isotype (International Typographic Image Education System) – is not exposed. Based on pictograms, Neurath isotypes are an important precursor to the digital vernacular language (from icons to icons) so familiar to us today. The exhibition does not include the cards of Gaza's devastation since October 2023, such as those made by the medico-legal architecture of the investigation agency, which prove among the most critical diagrams of our time, either.

It is important to note OMA's own connection with the Lagoon City. In 2009, he began his redevelopment of Fondaco Dei Tedeschi. Dating from the 13th century, although rebuilt in the early 1500s, the spectacular building had served as a public post office until it was acquired by Benetton and transformed into a luxury shopping center. Later, rented to the LVMH group, he became the home of the DFS retailer based in the latter. But at the end of last year, Fondaco suddenly announced its closure due to 100 million euros in losses.

The flush interior of Fondaco, with golden surfaces and red mechanical staircases, is a shiny but disturbing fusion of hypercapitalist skin of the 21st century stretched on a hundred -year -old skeleton. It would have been fascinating to see the diagrams for this renovation.

However, the dynamics behind the disappearance of the Fondaco, speaking as it does for the Glins on the global market paradoxically of Tiny Venice, binds to one of the most fascinating diagrams of the Prada spectacle.

Entitled “The World Model” (1972),, The monochrome flow graph connects subjects such as industrial capitalism, mortality, pollution and food production. Published as part of a report entitled THE Limits to growth For the Rome club, it illustrates the non-durability of uncontrolled economic and demographic growth. For this provocative image and many others, this show certainly deserves a visit.

May 10, November 24, Fondazioneprada.org

Find out first of all our latest stories – Follow the FT weekend on Instagram And XAnd register To receive the FT weekend newsletter every Saturday morning