Unlock the publisher's digest free

Roula Khalaf, editor -in -chief of the FT, selects her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

How many people should be that “American style business financing …

This is the argument that Donald H Chew makes in The manufacture of financing of modern companies, His ambitious attempt to update Adam Smith for the 21st century: “Because AS Smith suggested almost 250 years ago, it is the efficiency gains to find commercial uses for new technologies … by most private companies that end up with the bill for health, education and other forms of general well-being that most of us appreciate the most.”

Mercantilist supporters of the tariff war unleashed by President Donald Trump have no truck with Smith. Write in FT April 8 Peter NavarroThe main advisor to the President for Trade and Manufacturing said that the United States’s cumulative trade deficits since 1976 “have transferred more than 20 TN of American wealth to foreign hands” and that the United States has lost 6.8 million manufacturing jobs, mainly in China, during this period. He did not mention the advantages that America has collected from an open and competitive system. So there was never more time to redo the case of Smith.

Chew, the editor -in -chief of the Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, begins by describing what was wrong with “old -fashioned business funding” 50 years ago. In the late 1970s, he wrote, most large American companies were conglomerates. General Mills, for example, has spread to have breakfast cereals in a “all-season growth business”, buying toy manufacturers, play-do, “even small submarines”.

As long as the managing directors who chaired these transformations increased their earnings, they have kept their jobs without anyone asking their capital cost, and therefore if their empires created value. At a time in the 1970s, the S&P 500 lost almost half of its value; At the end of the decade, two professors from the University of Rochester wrote an article entitled “Can society survive?”.

On the surface, America continued to fight in the 1980s while Japan increased inexorably; The Nikkei 225 reached a record of 39,000 at the end of 1989 (today, the index is around 34,000). In 1992, 25 academics accused US companies of systematically under-infringement compared to their Japanese counterparts. But below the surface, something remarkable was happening. The Nikkei dropped 60% in the 1990s and did not Withdrawal of his peak from 1989 until February 2024. During this same period, the total S&P 500 yield in the United States was more than 3,000%.

Chew retraces the urgent moment of this renaissance of the fortune of American companies and scholarships, and the invention of “finance of modern companies”, to a classroom of Carnegie-Mellon University in 1957 when Merton Miller (Nobel Prize 1990) taught his first class in corporate finance under the supervision of Franco Modigliani (Nobel Prize 1985).

The objective of M&M, as they have known, was to transform the financing of companies from a decision -making process of siege of the pants – for example at the time and how to borrow money – in “a structured theory and a set of practices that would produce a better result”. In 1958, they published “the cost of capital, the financing of companies and the theory of investment”. This fundamental text threw the intellectual path of the barbarians who showed up at the doors of the American conglomerates in the 1980s and proceeded to dismantle them.

What followed are hostile control waves, share buybacks, replacement of equity by debt and taking private companies. The number of companies listed in the United States culminated at 7,562 in 1998. It is now less than 4,000. Chew estimates that new ways to manage and finance companies have contributed to “the growing social wealth of a large number – but in no case – of American citizens”.

The chewing is very good to transmit complex ideas in a clear language (the first equation appears only on page 27). But the structure of the book does not help to build its argument. After a convincing introduction, there are 10 tests, each based on the work of a leading theorist. They could be read on an autonomous basis, but together, they reduce the consistency of the main thesis of the book. Instead of a conclusion that brings together everything, the book is trying to try the advantages of the environment, social and governance (ESG), which already feels dated in the courageous new Trumpian world.

The tests cause two thoughts. First, if the 1970s were the period of finance of old-fashioned companies and the following 40 years were the period of financing for modern companies, are we now in a postmodern finance period of companies? A striking thing about the seven magnificent – Apple, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla – is how simple they are from a corporate finance point of view. NVIDIA, for example, has four times more money on its balance sheet than debt. The seven did not produce this value thanks to complex financial engineering.

The second question is: is there something really new in business financing? Major innovations – railways, electrification, internet, AI – caused productivity overvoltages that in turn allowed stock market bubbles. Technological companies represented 37% of American market capitalization at the beginning of 2025, but the railways represented 63% in 1900. The railway bubble collapsed, but the railways that financed continue to be part of the backbone of the American economy. The Magnificent Seven now enter a significant correction – so far this year, their market value has dropped some 2.5 billion dollars. But their technologies will continue to change the world.

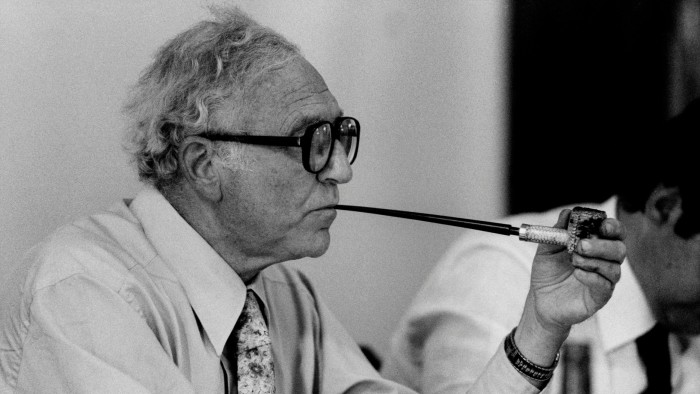

The Private Equity is one of the main drivers of the business financing period that chewing analyzes. It increased as dollar interest rates increased from 20% in 1980 to zero in real terms 40 years later, so that some financiers resemble innovative geniuses to replace equity with a cheaper debt. Paul Volcker, president of the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1987 and the most consecutive central banker during this interest rate cycle, was asked for the end of his life if he had seen real innovations in finance. He replied that there was only one – “the ATM machine”.

The manufacture of the finance of modern companies: a history of ideas and how they help build the richness of nations By Donald H Chew Columbia University Press £ 30 / $ 35, 328 pages

Join our online books online on Facebook in Ft Books Coffee And follow the FT weekend on Instagram And X