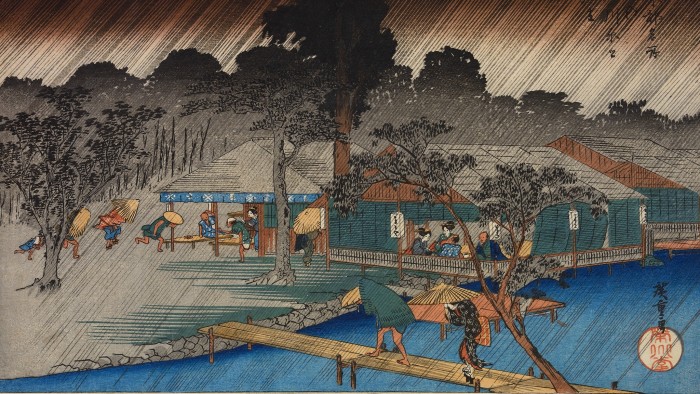

In the “Shōno – Sudden Showbour” by Utagawa Hiroshige (C1833-35), carrying a palanquin race for a shelter. Their bodies are leaning as a storm hides the sky in a gray with a half-light. Bamboo are looming like giant waves. The water that creates the theatrical district of Kyoto in “Sudden Shower Over Tadasugawara” (C1834) is even more angry: the black lines strike with percusance on the image, erase sunlight. One of the last great masters of the Japanese Ukiyo-e The wood print, among the many achievements of Hiroshige, are these representations of rain.

I look at “a sudden shower on ōhashi and Atake” (1857) for a while. Here, Hiroshige's rain creates fine threads that flow on the impression – although the black stained with storm clouds approaching the image suggests even more to come. Three men serve a single umbrella, caught up in the summer shower.

It is one of the many moments of the piercing atmosphere in the masterful investigation of the British Museum Hiroshige: Open road artistA large part of the collection of the American businessman and the connoisseur Alan Medaugh.

There is nothing particularly special in a landscape washed by rain. So why is the eye so irresistibly attracted to them? You can explain it in formal terms: how Hiroshige bisette its photo in dramatic diagonals of, say, bridge, water and shore.

Or maybe these images acquire their sense of movement of the impression itself. A block of carved cherry wood is inked with plant or chemical pigments: pink of carthame petals, the yellow of the arsenic sulfide, the white of ground shells or the Prussian blue. The mulberry paper is in a hurry on top, the printer rubbing it in circular movements with a bamboo bark cushion. The process is repeated with different colors, such as pieces of a puzzle.

The real answer, I think, is more difficult to express. Hiroshige is a lively observer of ephemeral moments – tracks, for example, travelers disperse when a storm breaks. His art concerns the way in which a whole landscape can change in this fraction of a second: tempo, texture, mood.

He was born in Edo, now Tokyo, in 1797 of a family of samurai at a low row, son of a fireman's goalkeeper. His childhood was tracked down by death – his older sister died at the age of three, her mother at the age of 12 and his father a year later. He was an apprentice to an artist from the Utagawa leading school – known for photos of beautiful women – shortly after.

Hiroshige experienced an era of dizzying change. He came to glory during the failure of cultures, disastrous famine, economic crisis and tensions within the elite of samurai. When he died a debtor at the age of 62, during a cholera epidemic, Japan had been “opened” by American gunboats. But you would not know any of this from the Hiroshige automobile Ukiyo-eWoodblock Prints of Edo's “Floating World”.

Such impressions, which sold for a little more than bowl of noodles, hairs with the revelers of the city, the courtesans and kabuki actors hitting a pose. They had to feel so tangible, familiar. No wonder many were also printed on bamboo fans (including Hiroshige designed 600). Has pop culture have already been so good?

However, in its first photos, it is the natural world that holds the eyes and stays in the mind for hours later: the moonlight, the frosted trees and the jumping clouds. In one, three statues of statues turn and turn in richly decorated outfits, but what really puts the impression in motion is the starry night behind them. In another, a woman walking in a thick snow stab her umbrella in the ground to test a safe place. It is a living detail.

Its representations of animals are also charming, whether it is an average hello descending at speed, or red eyes of a white rabbit looking at the full moon. Slatalier is his image of Rice God inari

I love rafts that slowly go to Kyoto in “Arashiyama in Full Bloom” (C1834). We are based on the bar; The other is lost in the wonder of cherry flower petals floating in the breeze. The speed at which they flow in the water is suggested by winding wakes lines, the blue of the river turning into brown white under the sunlight.

Bokashi is an accomplished shade technique by softening the ink with water, to control light and color. You see it everywhere in Hiroshige's work, black mountains wrapped in pink clouds in the development of the sky of early dawn. He hangs above a farewell of the auctions to a courtesan in “Morning Cherry Blossoms in the New Yoshiwara” (C1831).

These are not photos of the EDO pleasure district that made the name of Hiroshige, however. Instead, it was life on the road. In 1832, at the age of 35, the artist accompanied a delegation bearing shogun horse gifts to Edo to the emperor in Kyoto. He traveled the old 500 km Tōkaidō, a popular coastal motorway dotted with tea houses and hostels.

The scenes he saw flowing The fifty-three Tōkaidō stations. The series was a success that the original printing blocks were quickly exhausted. In Japan, everyone wanted these photos.

You can see why. In “Nihonbashi – Morning scene” (C1833-35), the entourage of a lord of Samurai rushes to carry luggage and plumey banners, their faces bowed and devoted. To another stop on the road, the landscape is almost completely drained in color, the snow by transforming it into a study in black and white. If you were a tourist traveling on this road, these prints were the perfect memory. For the chair traveler, they served as gates in other places.

The artist said one day about his work that they were “views that I had before my eyes and removed exactly as I saw them”. But that does not seem true for the foreign moments of Hiroshige. Take the prospect of its end of series 100 famous edo viewsin which a motif dominates the foreground to the distortion effect.

In “Suidō Bridge and Surugadai” (1857), a monstrous black carp thrown into the sky. But wait – this fish does not really steal. It is a festive kite, wrapped in the wind. Van Gogh, a collector passionate about Hiroshige, therefore admired the effect of kibble branches at “The Plum Garden in Kameido” (1857) that he recreated it in oils – the exhibition includes his prudent towels on gate doubled paper.

Hiroshige finished a series of photos around another route connecting Edo and Kyoto. Kisokaidō was an inner path that has gone through what is known today as Japanese Alps. You just need a glance at Hiroshige's “mountains and streams” by Hiroshige “Streams of the Kiso Road” (1857), its travelers overshadowed by gorges, waterfalls and a pure stretch of rock, to realize that it was a very different road from Tōkaidō.

And yet, even here, on the Perfide Kisokaidō, Hiroshige again found the moment ephemeral. “Karuizawa” (late 1830s) is an amazing image in an astonishing spectacle, proving the total mastery of darkness and Hiroshige light. In the middle of the night, a tired merchant arrived late in a post station. His servant stops to light his pipe by a fire of joy. The flames rise higher, inflating a brilliant smoke of smoke which briefly raises the dark – the emerald leaves of a revealed neighboring tree. It's a kind of magic.

As of September 7, Britishmuseum.org

Find out first of all our latest stories – Follow the FT weekend on Instagram And XAnd register To receive the FT weekend newsletter every Saturday morning