Unlock the publisher's digest free

Roula Khalaf, editor -in -chief of the FT, selects her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Is it time for us to redefine what we mean by professional success? Rutger Bregman thinks and his new book, Moral ambitionMake a quick and persuasive case to abandon the “work of the lamblance, or simply useless or simply harmful” and to do something more significant instead. It aims this book downright the “idealistic and ambitious” person of any age who works in council, law, finance and other well -paid sectors. (Yes, he looks at us, the readers ft.)

Bregman is not an ambition that lights up itself. The Dutch superstar historian has published several books and essays, including world bestsellers Humanity: a story full of hope (2020) and Utopia for realists: and how we can get there (2017). He became viral on Youtube in 2019 after calling billionaires to the World Economic Forum in Davos for their tax evasion tactics: “I feel like I was at a firefighters' conference and no one has authorized to talk about water.”

In the manifesto of this optimist, moral ambition consists in devoting “your professional life to the big challenges of our time, whether climate change or corruption, gross inequality or the next pandemic”. Inevitably, David GRAEBER And his concept of “bullshit work” makes an early appearance, but Bregman does not linger on the negative. He wants us to produce positive changes and we can start small. As he is customary in the modern manual “Change Your Life”, he inspires the reader through real examples.

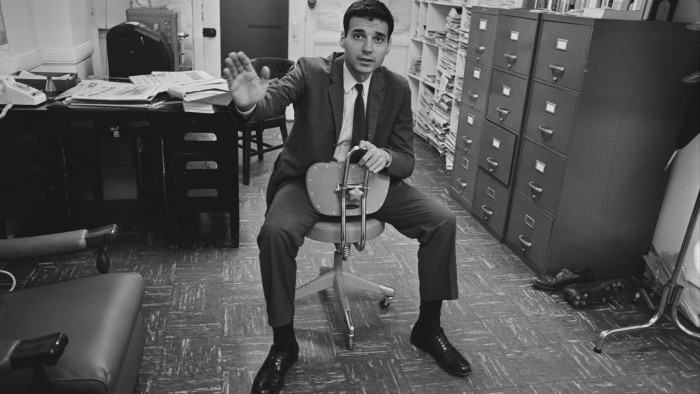

There is a game book here, and melting or joining “an Elite Corps of Drive Idealialists” is probably the best way to do it. The examples include Ralph Nader and the young lawyers who inspired to work with him to reform the law on complex issues such as food security and water pollution in the 1960s.

Bregman's flooded and persuasive writing style facilitates deep change. This helps that we read on the successful campaigns. The progress of the anti-slavery movement in Great Britain takes place throughout the book (“the abolitionist movement took place in a way of a quaker startup”) and Bregman shows how pragmatism led these activists to a society which was not interested in their objective.

Thomas Clarkson, an influential first abolitionist, rather focused on something that the country cared: the high number of death among British sailors on slave ships. About 20% of the crew, vulnerable to tropical diseases, died of dying during a given trip. “It is true, one of the greatest abolitionists of all time has moved its concentration to suffering among the authors. Psychologists call this tactic moral cropping. “”

The goal is to find new arguments for your idea that will change the world that will convince those who do not share your beliefs. This requires a compromise, and Bregman has no time for modern activists who fall with each other and drain potential allies due to minor misadventures or a lack of “intersectionality”: “You end up with a 100% pure, but 0% effective movement”.

At the start of Moral ambitionHe had struck me that Bregman's vision of some individuals creating a maximum gain for people and the planet could represent an emerging fight for forces for good against influence and the increasingly dark philosophy of the elite of Silicon Valley. Then, as if by magic, on page 48, there is an old photograph of the original “Paypal Mafia” of Peter Thiel Capital Capital, disguised as gangsters. “History is full of small action groups having a huge impact,” explains the author, reminding us that: “Thiel writes that we can talk about cult. “”

Bregman does not suggest that these founders of technology have a moral ambition (“it's questionable, of course, if these guys have made the world better”). He simply emphasizes that this concentration, tireless work and a dedication to a cause is effective. “If you want to change the world, you better join a cult. Or start yours. ”

Bregman's mission instead is to show that the more the cause is under the radar, the more important it is that intelligent people concentrate their efforts there. The most memorable example is the story of Rob Mather, a British commercial director who began to organize sponsored swimming to collect funds for a girl called Terre who had been seriously burned in a fire. Having collected enough money to make it financially secure for life, he extended and founded the Foundation against Malaria, which distributes mosquito nets treated with an insecticide. “What started as a Swim-A-Thon for Little Terra has become a campaign which, by conservative estimates, saved 100,000 lives.” AMF is, Bregman tells us, one of the most efficient non -profit organizations in the world, and it was built by an individual with a moral ambition.

None of this could have occurred if Mather had not watched a report in June 2003 on the Terra accident and published on Mumsnet, the parenting website, asking for ideas: “Charity Swim? Help by email? ” Sometimes it is a chance or a serendipity that takes us to new unexpected directions. And Bregman makes it look like the most exciting thing of all.

Moral ambition: Stop waste your talent and start making a difference By Rutger Bregman Bloomsbury £ 20 / little, Brown $ 30, 304 pages

Isabel Berwick is ft IT publisher and author of “the career to the test of the future”

Join our online books online on Facebook in Ft Books Coffee And follow the FT weekend on Instagram And X